The history of haggis: is Scotland's national dish really Scottish?

Love it or loathe it, haggis is firmly established as Scotland’s national dish - to the extent that it has become an indelible part of the nation’s cultural identity, along with whisky, bagpipes and shortbread.

The savoury meat pudding - consisting of sheep’s offal (most commonly lungs) mixed with suet, oatmeal, onion and spices, then boiled in a bag - is still served in huge quantities on Burns Night every year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScottish butcher Simon Howie, the company which now boasts the world’s best-selling haggis, reported record-breaking sales for its haggis range in the run-up to Burns Night in 2017.

"Gie her a Haggis" - Robert Burns helped popularise haggis in Scotland

The Burns connection goes back to his 1786 poem ‘Address to a Haggis’, in which he immortalised the dish as the “great chieftain o the puddin'-race”.

In the 232 years since Burns committed his love of haggis to poetry, the dish has become a symbol of Scottishness, and is traditionally served with neeps and tatties (mashed potato and turnip) - along with a dram of Scotch of course.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the origin story of haggis is as varied and divisive as its ingredients.

Ancient references to haggis-like foods

Long before it was known as ‘haggis’, similar foods were noted across culinary history, and a primitive version of haggis is even mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey, which was composed near the end of the 8th century BC.

In The Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson writes that the haggis is “the archetype of a group of dishes which have an ancient history and a wide distribution”.

And it was the Romans who were the first people known to have made use of haggis-like products, in order to feed their soldiers. Davidson writes that their version was usually made of pig offal, “enclosed in the clean caul of a pig” (the caul is a membrane surrounding the intestines).

A traditional Burns Supper in 1963 (Photo: TSPL)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe reason for the early popularity of haggis was pure necessity: when an animal was killed, the offal had to be eaten at once, or preserved in some way. By being salted, packed into a stomach and boiled, it would keep for a couple of weeks.

The French connection

The ‘Auld Alliance’ between the kingdoms of Scotland and France was formed in 1294, and it was another icon of Scottish literature, Sir Walter Scott, who claimed that the haggis had French origins.

Such is the influence of France on Scotland that it has been claimed that "haggis" comes from the French word "hachis", meaning minced meat.

Sir Walter Scott claimed that haggis was a French creation

However, there is little to suggest that the Waverley author was basing his assertion on historical evidence, and so perhaps it was his own imaginative romanticism of Scotland’s past, and its cultural affinity with France, which led to this claim gaining some credence.

Early English recipes

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the emergence of the printed word in the 15th and 16th centuries, there are the first references to early forms of the word ‘haggis’.

Food historian Catherine Brown claims the dish was invented by the English, citing references to ‘haggas’ in a book called The English Hus-Wife, dated 1615. In the book, author Gervase Markham referred to “this small oat meal mixed with the blood, and the liver of either sheep, calfe, or swine, maketh that pudding.”

Brown added that the first mention she could find of Scottish haggis was in 1747. Opponents of her claim cite the poem 'Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy', which is dated before 1520 and makes reference to ‘haggeis’.

However, there are haggis recipes that are older than these examples, predating even Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press.

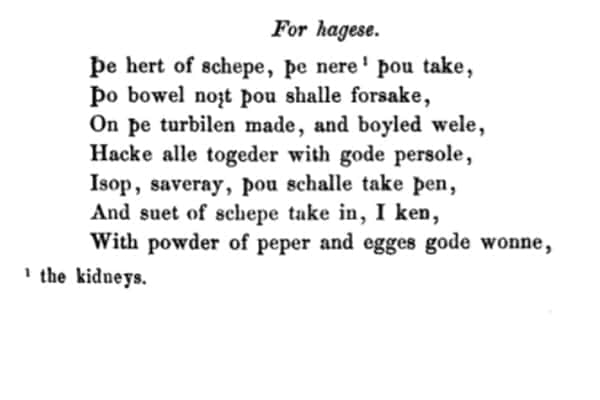

The recipe for 'hagese' in Liber Cure Cocorum

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn her book The Haggis: A Little History, the late TV chef and food writer Clarissa Dickson Wright identifies what she claims to be the earliest haggis recipe. “The first known cookery book is The Form of Cury (cookery), written in 1390 by one of the cooks to King Richard II,” she writes. “It contains a recipe for a dish called Afronchemoyle, which is in effect a haggis.”

Another oft-quoted haggis recipe can be found in the fascinating verse cookbook Liber Cure Cocorum, which includes a rudimentary recipe for “hagese”, making reference to ingredients like “hert of schepe”.

This manuscript is dated from around 1430 and originates from North-West Lancashire, which shows how the dish had gained popularity in England at the time.

A Nordic claim

However, Dickson Wright puts forward a convincing argument in favour of haggis having arrived not from England, or France, but with the Norsemen: "The alliance with France certainly goes far back, to William the Lion in the 12th century, but Scotland’s links with the Nordic lands are hundreds of years older than that."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe adds that she has "yet to find a single dish resembling haggis in the well-documented culinary history of France".

Haggis is more popular than ever (Photo: Shutterstock)

Embraced by Scotland

No matter its exact geographical origins - and it’s impossible to pinpoint one source given the lack of historical evidence - the nation which has taken the haggis to heart over the past two centuries is undoubtedly Scotland.

The first ever Burns supper was held at Burns Cottage in Ayr by friends of the Bard on 21st July 1801, the fifth anniversary of his death, and now Burns Night on 25 January is celebrated around the world.

The oatmeal element of haggis also adds to its Scottishness, and the Scots certainly have a taste for meat puddings - just look inside any chip shop in any town on a Saturday night for evidence of that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe famous haggis produced by MacSween of Loanhead (Photo: TSPL)

Scotland also has the world’s first dedicated haggis factory, opened by Macsween in Loanhead, south of Edinburgh in 1996, and the dish’s popularity has led to myriad innovations, from venison haggis and haggis pakoras, to vegetarian and gluten-free versions.

We may not be killing and eating our own meat these days, but we haven’t lost our appreciation for the ancient haggis.