The early life of town's first professor

Many years later, while recovering from rheumatic fever at Moffat in Dumfriesshire, Dr Robert Blakey set down to write his memoirs.

“The house in which I first saw the light is situated in Manchester Lane, next to the east side of the Methodist Chapel, in that narrow thoroughfare. My father, Robert Blakey, was a mechanic, chiefly employed by his uncle, a Mr Crawford, who was the first to establish the cotton trade in Northumberland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My father died two years after his marriage, when I was just nine months old, at the premature age of twenty-two. He was a youth of very religious habits, and the only relic I have of him is a copy of the hymn-book used in the Presbyterian Chapel, written at full length in his own handwriting. He invented a water-clock of a somewhat new construction, which was exhibited for some years, as a curiosity, by a Mr George Bates, a white-smith, well-known in Morpeth, where, I believe, some of his immediate descendants now reside.

“I have heard my relatives often mention that two days before my father’s death he sent for his minister, the Rev Robert Trotter, my uncle Robertson, and my grandmother, Mrs Laws, and, with a solemnity of manner, conjured them to bring me up in the Presbyterian profession, and in no other. They all with one voice made the promise; and he faintly ejaculated, “Now I die in peace”. This interview made a deep and lasting impression upon all present. Fifty years after, I have heard my Uncle Robertson recite the event with tears in his eyes.”

Dr Blakey refers to Manchester Lane as ‘that narrow thoroughfare’, but Manchester Street, as it now is, is perfectly normal. If you visit the Northumberland Communities website, and compare Wood’s map of 1826 with the OS map of 1860, it is obvious that there was a block to the north of Appleby’s Bookshop, which was demolished some time between those two dates. The cotton factory, where Robert Blakey Sen worked as a mechanic, was probably in one of the demolished buildings.

The Methodist Chapel that Robert was born next to was built by Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, who as a peeress was entitled to maintain a private chapel at any of her residences. She established several such chapels, but in 1783 was compelled to register them as dissenting meeting houses. Morpeth was never attached to a house, and so must have been built after that date. And while she generally preferred Gothic architecture, the chapel at Morpeth was built in Classical style. A capital carved with acanthus leaves, now in the old boiler room, was clearly the top of an attached column or pilaster, and was presumably a purely decorative feature on the front of the building.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

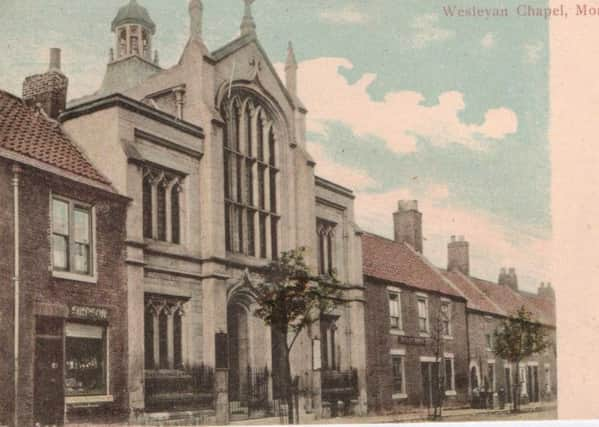

Hide AdLady Huntingdon died in 1791. When Robert was born, in 1795, the chapel still belonged to her Connexion, being its northernmost outpost. The Wesleyans bought it in 1809, partially rebuilt it in 1823, though probably with the same frontage, but demolished it in 1883 and replaced it with the present building.

Our postcard shows what was almost certainly the house where Dr Blakey was born, albeit from over 100 years later, by which time it was the Wesleyan Rooms. The Blakey house must have been the left of the two front doors.

It was very small, but his father and mother seem to have had exclusive occupation, which suggests that they were comparatively well-off. Another pointer to their social status is his father’s relationship to Mr Crawford. It links him with one of the more prosperous and influential families in Morpeth in the 18th century, but the evidence is tantalisingly incomplete.

A William Crawforth of Morpeth plumped (voted for one candidate only) for Lord Hartford in the county election of 1710, and either he or another William Crawford conveyed the site of the chapel in Cottingwood Lane to the Presbyterians in 1721. Three Crawfords, George, William and James, all resident and qualifying in Morpeth, voted in the election of February 1747-8, and again in 1774. This means that they were 40-shilling freeholders, in other words, men of property.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the ‘Cash Accompt’ of the Rev Robert Trotter, the Presbyterian minister, William Crawford was one of the collectors of the chapel dues. His first payment to the minister was in 1758, and he carried on until 1780, when he died. Yet another William Crawford, wine merchant in Morpeth, appears in the Universal British Directory c.1793 and both the Morpeth Parish Registers, under ‘Births of Dissenters’, and the Presbyterian registers record a number of Crawford births.

The day book of a local solicitor, William Woodman, also shows that Robert Blakey’s Crawford relatives were indeed men of substance. Robert spent his teenage years in Alnwick, but returned to Morpeth, and in 1836 paid out £1 18s. 8d., a large sum then, for a copy of the will of a Mr Crawford, deceased, and to have it perused by the solicitor. This man must have died leaving no direct heirs, and despite leaving a will, died intestate, but I cannot find out who he was or where he lived.

Mr Woodman also did the same service for a lady called Margaret Crawford, presumably a more or less distant cousin of Robert Blakey, but there is no record of either of them receiving anything from the estate.

Robert goes on: ‘When about six years of age, I was placed entirely under the care of my maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Laws, who lived alone in one of the oldest and most rickety houses in Morpeth. It had been built of pure clay or mortar, and was next door on the west side of the old Phoenix Inn, and in the midst of the sheep-market, in Bridge Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She was very old, between seventy and eighty, but of wonderfully active powers, both of body and mind. She was well-known to the whole town for her zeal and knowledge of theology — that is, Presbyterianism.

“The Westminster Confession of Faith was quite at her fingers’ end; and no doctrinal point contained in the treatise could be mentioned for which she could not readily quote the scripture proofs.”

This was a crucial turning point in Robert’s life, and formed the starting point of his later career.

• I wrote last week that my grandmother described her terraced house as a ‘mansion.’ This was wrong. My wife reminds me that the word was “villa”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOrdinarily, both words imply large houses for the very rich, but in Edwardian estate agent parlance, a villa was a larger, but not very large terraced house.

My grandmother told me a curious story about the houses where she lived. When built, they were intended for the warders at Leicester prison. On the face of it this was a good idea. The warders had a steady income, and the prison was only a mile away, but so few warders could afford them, that they were eventually let or sold to a wider public.