Morpathia history article: Downing 2

He began his diary in January 1660, just as General Monck was crossing the Tweed to march to London. In June, when he was all-but sure of becoming Clerk of the Acts in the Navy Office, he wrote:

“To Sir G. Downing ... He is so stingy a fellow I care not to see him; I quite cleared myself of his office, and did give him liberty to take anybody in.”

And in March 1662:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This morning we had news that Sir G. Downing, like a perfidious rogue, though the action is good and of service to the King, yet he cannot with a good conscience do it, hath taken Okey, Corbet and Barkestead at Delfe.”

These men had signed Charles I’s death warrant and his son wanted them alive.

On the 17th:

“Last night the Blackmore Pinke brought the three prisoners to the Tower ... the Captain tells me, the Dutch were a good while before they could be persuaded to let them go, they being taken prisoners in their land. But Sir G. Downing would not be answered so, though all the world takes notice of him for a most ungrateful villaine for his pains.”

Downing’s capture and rendition of them was extrajudicial, but what appalled Pepys more, and everybody else since, is that it was Okey who “gave him his first bread in England” sixteen years before. Okey had, moreover, told him of his intentions and Downing had assured him and Barkestead that in Holland they would be “as free and safe there as himself”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1663, he was rewarded for his treachery with a baronetcy.

Whatever his feelings, however, Pepys had no doubt of Downing’s ability. In 1667:

“The new Commissioners of the Treasury have chosen Sir G. Downing for their secretary; and I think in my conscience they have done a great thing in it; for he is active and a man of business, ... so that I am mightily pleased in their choice.”

And in 1668:

“He told me that he had so good spies, that he hath had the keys taken out of De Witt’s pocket when he was a-bed, and his closet opened, and papers brought to him ... and carried back and laid in the place again, and keys put into De Witt’s pocket again.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDowning was fluent in Dutch and observed how De Witt, a brilliant financier, managed the taxation there. He tried to persuade the government to adopt similar practices here, though with only partial success, and was made Commissioner of the Customs in 1671 at a salary of £2,000 p.a.

As an MP he introduced appropriation of supplies, whereby the Commons could require funds they voted to be spent on their intended purpose, and the King himself said that he wanted the Treasury managed by “rough and ill-natured men, not to be moved with Civilities or Importunities in the Payment of Money.”

Downing also promoted the Navigation Acts, which prohibited foreign vessels from carrying goods to or from Britain, and laid the basis of Britain’s future domination of world trade.

Although he was MP for Morpeth for 25 years, Downing had little to do with the town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdElection results apart, the only thing Hodgson records of him is his name on a deed of the Earl of Carlisle giving £5 per year to Morpeth Grammar School out of his Northumberland estates – which didn’t cost Sir George anything at all.

Having said that, he must have had to dip into his pocket to secure his election for the three parliaments in which he represented Morpeth. Given his experience with spies and informers, he may have preferred giving generous bribes rather than relying on the uncertain results of public benefactions.

Sir George bought large estates in Cambridgeshire and was reputed to be the richest man in England. He lived at Gamlingay and died there in 1684, Lady Frances having predeceased him by a year. They are buried in the nearby parish church of Croydon.

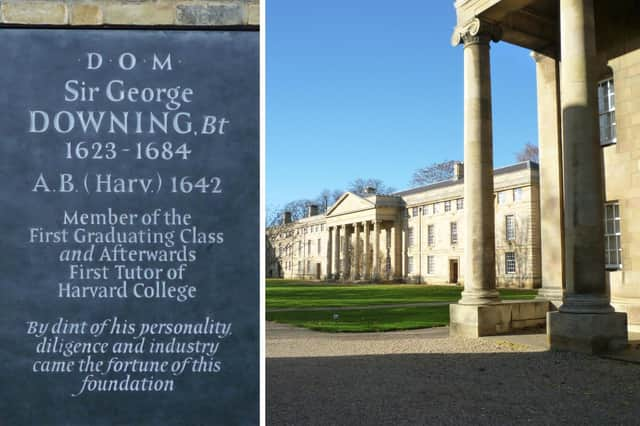

What about Downing College? Sir George was sneered at behind his back for his modest origins and for being educated at Harvard, a mere colonial institution. His own object was to found a dynasty, not a college, and in this he succeeded, being allied by marriage to the Howards, one of the great families of England.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis son, also Sir George, married into yet another great family, the Cecils. His wife was Lady Catharine Cecil, daughter of the Earl of Salisbury.

Their son, another Sir George, third baronet, was brought up in Shropshire in the household of his mother’s sister, Lady Mary Cecil Forester. He was married at fifteen – “by procurement and persuasion of those in whose keeping he was” – to his 13-year-old cousin, Mary Forester.

There was no hurry for them to live together, so George went away to Europe on his grand tour. Before doing so, he asked Mary not to go to court.

He seems to have loved her in his own way – they had after all been brought up together – and when he heard from a friend that she had gone to be a maid of honour to Queen Anne he was deeply upset.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he got back, it was obvious that the marriage was over. Mary was in the midst of a social whirl while he preferred to live quietly at home. The marriage was never consummated and the couple jointly petitioned for a legal separation. It was granted, but meant that while either lived, neither of them could remarry and have legitimate children.

This Sir George built a fine house called Gamlingay Park. He had a daughter, Elizabeth, by his mistress Mary Townsend, formerly a domestic servant, but his heirs were his cousin, Jacob Downing, and three other male cousins. In his will he stipulated that if the male line died out, his estates and fortune should be used to found “Downing’s College” at Cambridge.

Sir Jacob died in 1764, the other three being already dead. His widow claimed the estate and when the parties acting on behalf of Cambridge University – a miscellaneous group including several rather distant female relatives, the masters of Clare and St John’s colleges, and the archbishops of Canterbury and York – won their case in 1769, she and her nephew, to whom she tried to leave the property, demolished Gamlingay Park in 1776.

She died in 1778, but her second husband and nephew still held out for another twenty years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDowning College was eventually founded in 1800. William Wilkins, a young classical architect, designed it on a grand scale, but the estates were so depleted by neglect and by the law costs that only two of the four planned ranges were built by 1820, although the East Range remained unfinished for another fifty years, and it wasn’t until 1953 that a third range to the North was completed.

(Portraits of Sir George and Lady Downing by kind permission of the Master, Fellows, and Scholars of Downing College in the University of Cambridge. Copyright reserved.)