Jim Herbert: Berwick’s role in the Jacobite rebellions

I leave the political commentary for others in this paper. However, I was reminded of the last time some in Scotland attempted to break away from the Union. I had a request for information about General William Draper and Berwick in the 18th century. General Draper fought in the Philippines during the Seven Years War and his grandfather was from Berwick. What side was Berwick on during the Jacobite Rebellion?

Scotland and England became a United Kingdom with the Union of the Crowns in 1603 when James VI of Scotland became James I of England. In 1685 Charles II was succeeded by his son, James VII & II. James was deeply unpopular in England because of his religion. He was the first Catholic monarch of Great Britain and the political elite believed him to be pro-French as well as pro-Catholic. An early coup failed but James’ behaviour led to his deposition by William III of Orange in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. The Anglicisation of Scotland was complete with the Act of Union in 1707.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOr so it was thought. Despite earlier uprisings, what is usually called the First Jacobite Rebellion took place in 1715 after George I became King a year earlier. The Scottish Earl of Mar declared James Stuart (son of James VII & II) the rightful heir, raised an army in the Highlands and swept south.

In Berwick, the guild toasted the new King but were alarmed when the Northumberland MP, Thomas Forster of Bamburgh, raised a force to join the uprising. Ten companies, each of 40 men, were formed to defend the town. Sympathisers were arrested and thrown in jail at the town hall (the one prior to ours). Famously, Launcelot and Mark Errington overcame the garrison at Holy Island Castle, were arrested but later escaped by digging a tunnel out of their cell (part of the café under the present Town Hall).

The Jacobites marched south from Leith in September that year, threatening an attack in September. The military engineer, Captain Thomas Phillips commanded that houses at the lower end of Castlegate be demolished to allow his cannon to have a clear line of fire. The Jacobites moved to Kelso instead and it took five years for the property owners to get their money back. The First Rising came to nothing and the “Old Pretender” escaped to France in 1716.

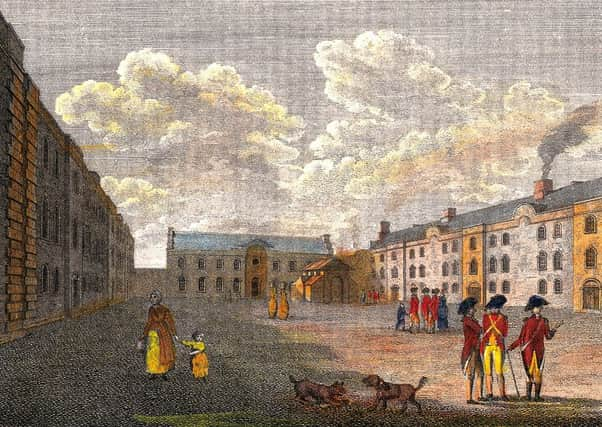

While it had been in the planning stages beforehand, this rebellion and threat to Berwick undoubtedly concentrated government minds and Captain Phillips was put in charge of building Berwick Barracks, the first purpose built barracks in Britain, between 1717 and 1721.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn July 1745 rebellion was in the air once more when sympathisers tried to supplant George II with “Bonnie Prince Charlie”, Charles Stuart – the “Young Pretender”. By September, Edinburgh had surrendered to the Jacobites. Dutch and Hessian troops moved through Berwick to join Sir John Cope at Dunbar. They were soundly defeated at Prestonpans on 20th September 1745 and Cope and his troops fled south to Berwick.

This gave rise to the rebel song, ‘Hey, Johnnie Cope, are Ye Waukin’ Yet?’ which includes the lines:

“Sir Johnie into Berwick rade,

Just as the devil had been his guide;

Gien him the warld he would na stay’d

To foughten the boys in the morning.

Says the Berwickers unto Sir John,

O what’s become of all your men,

In faith, says he, I dinna ken,

I left them a’ this morning.”

The town was put on alert again first as the Jacobites moved south to Derby and then on their retreat back. Government expeditions, most notably by the Duke of Cumberland passed through Berwick to great acclaim by (most of) the townspeople. The army was greeted with food and drink and sympathisers’ windows broken. After his victory at Culloden, Cumberland marched back and was wined and dined in Berwick. A lavish ball was held in his honour and he was given the Freedom of the Town in a gold box. One of the Elizabethan bastions, previously called Middle Mount was renamed Cumberland Bastion in his honour.