NATURE NOTES: The underwater forests that hold our coastline together

They sway gently, though there is no wind. In summer, pale flowers bloom and pollinators busy themselves.

Yet these are not the buzzing bees or kaleidoscopic butterflies of the world above.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInstead, small crustaceans, ‘the bees of the sea’, carry pollen from one plant to another.

For we are underwater now, at high tide, and these are seagrass meadows – little known, but vitally important.

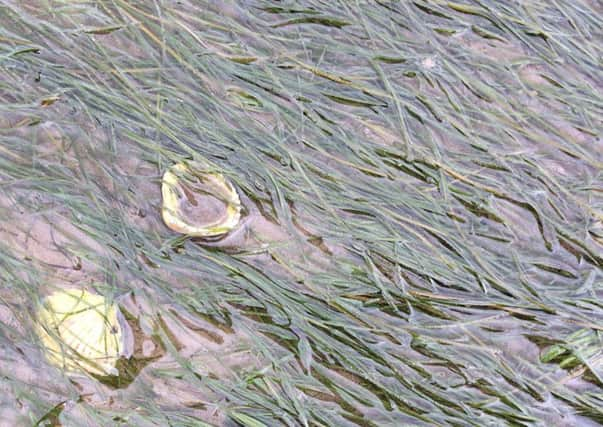

Lindisfarne boasts the largest seagrass, or eelgrass, meadows in north-east England, with a large intertidal area providing a valuable site for the narrow-leaved (zostera angustifolia) and dwarf eelgrasses (zostera noltii).

Once terrestrial plants, they moved back to the sea many millions of years ago. Low tide exposes their slim leaves, slick against mud and sand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the tide recedes, I pause a moment on the causeway and see flying north low skeins of light-bellied Brent geese, dark against the heavy winter sun.

They settle on the shining mudflats and form bowing silhouettes at the water’s edge.

These geese – half of the entire world population – have come a long way for this seagrass. So far as one can tell, it seems to satisfy.

Beyond the Brent appear a supporting armada of wigeon with copper heads and a relieved, whistling call ‘phew, phew’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeagrasses provide essential nutrients for these migratory waterfowl, whose presence each autumn transforms the Reserve.

Year-round, decaying seagrass leaf litter provides food for small crustaceans, bivalves and worms living in the intertidal area.

Wading birds, with their slender beaks and long legs, are not shy to make the most of the smorgasbord of invertebrates.

Seagrass meadows also provide valuable nursery grounds for many tiny fish, who take shelter in these underwater forests.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhere Nemo sheltered among bright corals, here – in more temperate climes – codling flit through the grasses, dark shapes turning to bronze in the sunlight.

As juveniles, these are low on the food chain but survivors will become sleek muscular predators, scouring the seas for smaller fish, crustaceans, worms and molluscs.

And cod, in turn, may find themselves prey to the coast’s booming grey seal population or fished commercially, by the area’s many local fisheries.

So much begins with seagrasses – and yet even this is a mere beginning.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is no exaggeration to say that they hold the coastline together; their thick vegetation limits sediment flow and helps to prevent coastal erosion.

More importantly still, seagrass meadows capture and store carbon more effectively even than rainforests, reducing the impact of climate change. They are known as ‘blue carbon’ ecosystems.

According to the environmental charity and research platform Project Seagrass, one hectare of seagrass can produce 100,000 litres of oxygen per day. Over a year, one hectare can store the equivalent carbon emissions of an average small UK car.

One hectare can support 80,000 fish and 100million invertebrates. We are losing one hectare of seagrass per hour worldwide.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeagrass is disappearing – its decline driven by a combination of natural causes like storms and disease, and human activity such as climate change, coastal development, pollution, decreased water clarity and physical disturbance.

These hidden meadows, teeming with life, are slow to recover from damage.

The Brent call to one another, their distinctive rolling cry. A curlew passes – so dignified in repose, yet comical in its hurried stride. A little egret stabs its black beak into the water.

I breathe in the air, the scene. So much might be lost. And yet, so much might be saved. Seagrasses have incredible power and potential.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough vulnerable to climate change they could also play a powerful role in combatting it. We might just be able to save one another.

Download the free SeagrassSpotter app to help Project Seagrass to map and monitor seagrass worldwide or visit their website to find out more.

Ceris Aston is an apprentice at Lindisfarne Nature Reserve and author of thewordsandthebees.blog. Follow her on Twitter: @insocrates