British pushed forward by gallant, brave and determined soldiers

It began with the Battle of Messines (June 7-14) which was a significant success for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Part two focused on preparations for the second phase of the campaign and the Battles of Pilckem (July 31 to August 2) and Langemarck (August 16-18), to the end of August 1917. Part three deals with the third phase of the Offensive and second phase of the 3rd Battles of Ypres (Passchendaele) covering September up to and including October 4.

CONTINUATION AND CONTROL

Following the Battle of Langemarck Sir Douglas Haig, the BEF’s Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), effectively removed Sir Hubert Gough, 5th Army C-in-C, from command of the Flanders Offensive. On August 25, command returned to Sir Herbert Plumer (2nd Army) who demanded a three-week pause in operations while preparations were made for a series of small-scale advances, always under the umbrella of supporting artillery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe plan was to secure the Gheluvelt Plateau in four steps with six days between each to allow time to bring forward artillery and supplies. Plumer enjoyed much greater concentration of artillery than was available to Gough who commanded the second phase of the campaign (covered in the July 27 edition of the Gazette). This middle phase of the Offensive illustrated good tactics, but when the weather changed, again, it was impossible to move artillery pieces or bring forward sufficient artillery ammunition, in consequence even more limited objectives had to be set/accepted, for example, the Passchendaele Ridge rather than striving for the coast.

BATTLE OF THE MENIN ROAD BRIDGE: SEPTEMBER 20-25

The British plan for the Battle of the Menin Road Bridge focused on using artillery to destroy German concrete pill-boxes and machine-gun nests in the battle zones being attacked and to engage in more counter-battery fire. Whereas the number of artillery pieces available during the Battle of Pilckem was one gun every 10 metres or so, for the Battle of the Menin Road Bridge, the British deployed one gun every four to five metres. They had 575 heavy and medium pieces of artillery and 720 field guns and howitzers. More effective use of aircraft was made for systematic air observation of German troop movements, to avoid the failures of previous battles, where too few aircraft crews had been burdened with too many duties flying in poor weather.

On September 20, the Allies attacked on a front of 13,300 metres and captured most of their objectives, to a depth of about 1,400-1,500 metres by mid-morning. German counter-attacks failed to gain ground or made only a temporary penetration of the new British positions. Weather conditions were good when the Battle of the Menin Road Bridge was launched. The well-planned and prepared attack highlighted weaknesses in the German system of flexible defence tactics – their counter-attack divisions were held too far back. The effectiveness of British tactics caused the Germans to revert to front-line defence.

Minor attacks took place after September 20, as both sides sought to gain better positions and reorganised their defences. A German attack on September 25 recaptured pillboxes at the south-western end of Polygon Wood, but, next day, the German positions near the wood were swept away in the Battle of Polygon Wood.

BREAK-THROUGH: AN UNOBTAINABLE GOAL

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaig wanted a campaign that would have a strategic outcome, which conditioned many of his decisions. Invariably, unobtainable objectives were set aiming for the BEF to smash through German defences but the tools and resources to do so were never available, indeed they did not then exist.

In the First World War, there was no ‘breakthrough’ instrument – tanks of the day could help the BEF break in to German defence lines, but they were not the breakthrough weapon they became in the Second World War. Given the preponderance of machine guns and sophistication of German defences on the Western Front, the 5 Cavalry divisions available to the BEF were never an option as a breakthrough instrument, in truth, they were largely ineffective.

BITE AND HOLD

If Haig and Gough had stuck with Plumer’s idea of a series of bite and hold operations, it may have held German attention and resources, directing them away from the French and Russians without moving the British line forward too much. Bite and hold was within the realms of the possible whereas, at that time, breakthrough was not. The problem did not lie at tactical level rather with the concept of bite and hold and the law of diminishing returns as ground churned up, which prevented forward movement of guns. Although the BEF in 1917 was more capable than in 1916 it would be hard to over-emphasise how much more formidable it was to become in 1918 compared to 1917.

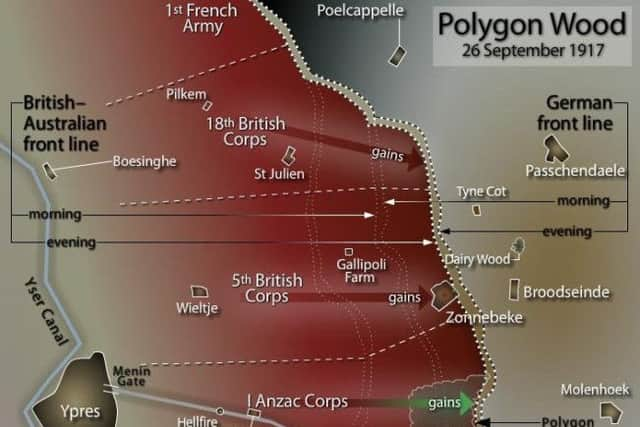

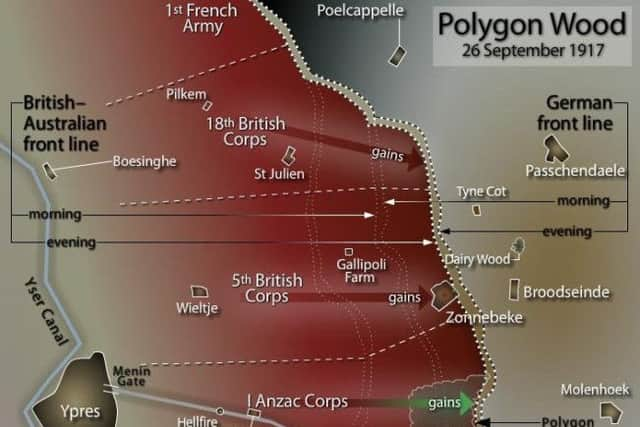

BATTLE OF POLYGON WOOD: SEPTEMBER 26 – OCTOBER 3

The focus for the next attack now lay between the Ypres-Roulers railway and the Menin Road, where 5th Australian Division was required to push forward and capture the whole of Polygon Wood and the southern section of Zonnebeke. The Australians were flanked on both sides by British units which were also required to advance a considerable distance. 5th Australian Division encountered little resistance when it attacked Polygon Wood. The German Flandern 1 line (fourth line of defence) was breached. The men of the adjoining 4th Australian Division also reached their objectives without difficulty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo the south, 39th Division did not manage to break through to its final objective. Its men came under fire from all sides and had no choice but to pull back. Further north troops of the 3rd Division were seriously handicapped by the muddy conditions of the Zonnebeek. They got bogged down and had to dig themselves in 500 metres short of their final objective. Most of the attack’s objectives were taken and the offensive was regarded as a relative success. German counter-attacks were dealt with effectively and the Germans sustained large numbers of casualties, particularly from artillery fire.

BROODSEINDE: OCTOBER 4

The Battle of Broodseinde was a spectacular success for the BEF which advanced about one kilometre across a front two kilometres wide. It was the last assault Plumer could launch with the benefit of clear weather. The artillery arm was again key with 180 18-pounders and 64 4½” Howitzers deployed on a narrow front. One thousand German prisoners were captured, but it was not a cheap victory with 1,853 New Zealand casualties, 25 per cent of whom were killed.

Many commentators describe Broodseinde as a black day for the Germans. Along with gains made during the Battle of Polygon Wood, Broodseinde established British possession of the ridge east of Ypres. As commander of Army Group Rupprecht, with overall responsibility for German forces facing the BEF, Field Marshal Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, began at one point to prepare for a major withdrawal, however, the weather broke again at the beginning of October, which effectively saved the Germans from having to do so.

2ND LIEUTENANT WILLIAM BICKERTON

2nd Lieutenant William Bickerton served with the Machine Gun Corps (Infantry), 56th Battalion. He was the third son of Thomas and Mary (née Robinson) Bickerton, of Crag View, Longhoughton. Educated at Duke’s School, Alnwick, before the war William was a grocer. Bickerton is recorded in ‘de Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour 1914-18’ (2003 reprint by Naval and Military Press; originally published in 1922; Part 5; page 14) as having joined the Northumberland Fusiliers early in 1915, quickly attaining the rank of Sergeant, then serving as Machine Gun Instructor at various training camps in England.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant on March 28, 1917, joining the Machine Gun Corps and serving with the British Expeditionary Force from June 3 of that year. He was killed in action at Hollebeek on September 20, 1917. His Captain wrote: ‘Your son was killed in the early morning of September 20, shortly after commencement of the great battle in which we took part. He was killed instantly by a shell whilst gallantly commanding his guns. Our machine guns did a lot of execution, and the enemy did his best to find us, I cannot tell you how deeply sorry I am personally at the death of your son. William was one of my best officers and highly popular with all of us. Our part of the attack involved a great deal of preparation. He was a keen and gallant fellow. I am sure you must be proud of him. His place here in this company will be difficult to fill.’

Another fellow officer, Lieutenant Eckersley, wrote: ‘He was an excellent and fearless officer, and was highly esteemed by both officers and men.’ 2nd Lieutenant Bickerton is buried at Oxford Road Cemetery, Ieper, and he’s commemorated on Longhoughton War Memorial.

DISTINGUISHED CONDUCT MEDAL AWARD

Petty Officer Thomas Edgell, DCM served at Passchendaele with the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, Royal Naval Division, Hood Battalion. He died of wounds received. Born at Alnwick on November 25, 1879, Edgell left a wife, Alice, who lived at 277 Maypole Street, Ashington. Before the war he had been a miner.

Earlier in 1917, Petty Officer Edgell was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for action at Grancourt between February 3 and 5. His citation is given in the March 26 edition of the London Gazette: ‘For conspicuous gallantry in action. He got his machine guns into action under heavy fire and greatly assisted in repelling a strong enemy counter-attack. He set a fine example of courage and initiative’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Distinguished Conduct Medal was instituted by Royal Warrant on December 4, 1854, during the Crimean War, as an award to Warrant Officers, non-commissioned officers and men for ‘distinguished, gallant and good conduct in the field’. For all ranks below commissioned officers, it was the second highest award for gallantry in action after the Victoria Cross, and the other ranks’ equivalent of the Distinguished Service Order, which was awarded to commissioned officers for bravery. Edgell is buried in Douai British Cemetery, Cuincy, and he’s commemorated on Alnwick War Memorial.

EMIGRANTS RESPONDED TO THE MOTHER COUNTRY’S CALL TO ARMS

Lance Corporal George Foggin was one of many local men who had emigrated to one of the Dominions in the early years of the 20th century but answered the call to arms. Having served with the 12th Northumberland Yeomanry (Territorials) before emigrating to Australia, he enlisted into the Australian Infantry Force (AIF) on January 10, 1916.

Born in 1885 at Glanton, Foggin was the second son of George Foggin, a grocer, and his wife Jane. His older brother was Robert, and he had three younger brothers (Thomas, John and William) and a sister, Catherine. George Senior died in 1905. His widow continued to run the grocery shop in Front Street, Glanton, following the death of her husband. Her son George married Margaret Thompson in 1909 but the 1911 Census reveals that, aged 26, he was, then, an out-of -work coachman. There was no mention of his wife in the census return, but she may have been visiting family at the time. The return was completed and signed by George Jnr on behalf of the family and shows there had been six children born in the family, but only five had survived.

On May 25, 1911, just after the census, Foggin boarded a ship for Fremantle, Western Australia, leaving his wife behind. On October 10, 1912, one of his younger brothers, Thomas, and George’s wife Maggie followed. Following Margaret’s arrival in Australia, she and George set up home at 126 Richardson Street, Boulder, Western Australia. The Australian attestation papers of George and Thomas show them both as miners – Thomas survived the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFoggin’s death was reported in the Newcastle Journal of October 13, 1917: ‘FOGGIN - Killed in Action, aged 32 years. George Foggin, Australian Imperial Force, dearly beloved husband of Maggie Foggin, Boulder City, Western Australia. 2nd and dearly loved son of Jane and the late George Foggin, Glanton’ He is commemorated on the Rolls of Honour in St Bartholomew’s Church, Whittingham, and Glanton Presbyterian Church.

MORE LOCAL FAMILIES LOSE TWO OR MORE SONS

Private William Hall was a native of Bamburgh, the son of Robert and Elizabeth Hall who lost three sons in the war. He, too, was an emigrant who responded to the call to arms by serving with the AIF’s 28th Battalion. His brother Phillip was 23 when he died of wounds sustained at Gallipoli. He served with the AIF’s 16th Battalion and died on May 16, 1915. He is buried at Alexandria (Chatby) Military &War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt, and the brothers are commemorated on Bamburgh Castle War Memorial. Searches reveal that Phillip was a paper hanger and painter by trade. He emigrated to Australia, aged 20. The third brother lost was Private Albert Hall who served with the Royal Engineers, 15th Field Company. He was killed on May 27, 1918, aged 31, and is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial. His widow, Rebecca, lived at The Wynding, Bamburgh.

Private John Storey enlisted at Guisborough and was serving with Alexandra, Princess of Wales’ Own (Yorkshire Regiment), 10th (Service) Battalion when he was killed in action. Storey was born in 1885, the son of Annabella (née Slassor) and the late John Storey who had married in 1878. In 1911, he was single and employed as domestic gardener, living with five other gardeners at Bothy, Ravensworth Castle.

The Storey family was one of about 30 local families to lose two or more sons in the First World War. John’s older brother William was killed in action July 1, 1916, while serving in the same battalion of the same regiment as his younger brother. William, who was a shepherd before the war working for George and Elizabeth Weatherall on their farm at Whittingham, is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial while John is buried at Tyne Cot Cemetery. They are both commemorated on the Roll of Honour at St Bartholomew’s Church, Whittingham.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• The fourth part of this article, dealing with the final and most controversial phase of the 3rd Battles of Ypres (Passchendaele), will be published in a few weeks. As always, anyone with information on ancestors with a wider Alnwick connection who were lost in the 3rd Battles of Ypres is encouraged to contact the author via [email protected]Roll of Honour: September 1 to October 4, 1917

For each entry, the format is the name and rank; regiment/battalion; date of death; age; and where commemorated (or buried, if found).

2nd Lieutenant (Temporary) Norman Archibald Hunter; Northumberland Fusiliers, 26th (Service) Battalion (3rd Tyneside Irish), A Company; 3 September; 22; Hargicourt British Cemetery.

Private Thomas Gregory; Lancashire Fusiliers, 1/6th Battalion Territorial Force; 6 September; 34; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Frederick William Thorborn; Alexandra, Princess of Wales’ Own (Yorkshire Regiment), 2nd (Home Service) Garrison Battalion, transferred to Labour Corps, 64th Company; 7 September; 35; Bard Cottage Cemetery.

Private Thomas William Adams; Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, 6th (Service) Battalion; 9 September; 22 Level Crossing Cemetery, Fampoux.

Lance Corporal John Robert Miller Cairns; Northumberland Fusiliers, 23rd (Service) Battalion (4th Tyneside Scottish); 9 September; 27; Hargicourt British Cemetery.

Lance Corporal Norman Patterson; Northumberland Fusiliers, 20th (Service) Battalion (1st Tyneside Scottish); 9 September; Unknown; Thiepval Memorial.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Arthur Agar; Northumberland Fusiliers, 24th/27th (Service) Battalion (1st/4th Tyneside Irish); 10 September; Unknown; Thiepval Memorial.

Private Thomas Dunn; Northumberland Fusiliers, 20th (Service) Battalion (1st Tyneside Scottish); 10 September; 24; Thiepval Memorial.

Private Adam Ross; 57th Field Ambulance attached to the Bedfordshire Regiment, 2nd Battalion; 11 September; 24; Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery.

Corporal Hugh Streener; Northumberland Fusiliers, 1/7th Battalion Territorial Force; 15 September; Unknown; Hibers Trench Cemetery, Wancourt.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Thomas Hume; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion; 17 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Private John Thomas Baston; Prince of Wales’ Own (West Yorkshire Regiment), 11th (Service) Battalion; 20; September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

2nd Lieutenant William Bickerton; Machine Gun Corps (Infantry), 56th Battalion 20 September 29 Oxford Road Cemetery, Ieper.

Private George Anthony Donohoe; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion Territorial Force; 20 September; 19; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate William Hall; Australian Infantry Force (AIF), 28th Battalion; 20 September; 37; Ieper (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Private Thomas Scott; King’s (Liverpool Regiment), 1/7th Battalion Territorial Force; 20 September; Unknown; New Irish Farm Cemetery.

Private Albert Edward Taylor; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion; 20 September; 26; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Lance Corporal Robert Todd; Northumberland Fusiliers, 11th (Service) Battalion, C Company; 20 September; 21; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Albert John Caws; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion; 20 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery). Private Stanley Makins; Northumberland Fusiliers, 1/7th Battalion Territorial Force; 20 September; 27; Arras Memorial (Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery).

Private Ambrose Townsley; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion; 20 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Private Peter White; Northumberland Fusiliers, 10th (Service) Battalion; 20 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Able Seaman David Taggart Henderson; Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, Royal Naval Division, Hood Battalion; 21 September; Unknown; Point-du-Jour Military Cemetery, Athies-les-Arras.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate James Sanderson; Durham Light Infantry, 12th (Service) Battalion; 21 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Corporal Ernest Smetham; Northumberland Fusiliers, 11th (Service) Battalion; 21 September; 23; Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

Petty Officer Thomas Edgell, DCM; Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, Royal Naval Division, Hood Battalion; 24 September; 37; Douai British Cemetery, Cuincy.

Private William Straughan; Labour Corps, 46th Company; 25 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Arthur Cockburn; Australian Light Infantry, 56th Battalion; 26 September; Unknown; Ieper (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Lance Corporal Richard Keay Hutchinson; Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st Battalion; 26 September; 26; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Sergeant Michael Mallon; Machine Gun Corps, 207th Company; 26 September; 30; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Private Joseph O’Brien; East Yorkshire Regiment, 8th (Service) Battalion; 26 September; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate James O’Hare; Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st Battalion; 27 September; Unknown; Hermies Hill British Cemetery.

Lance Corporal George Foggin; Australian Infantry Force, 16th Battalion; 28 September; 32; Ieper (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Private Frank Gibson; Northumberland Fusiliers, 14th (Service) Battalion (Pioneers); 28 September; 22; The Huts Cemetery.

Private Isaac Frazer; Cheshire Regiment, 9th (Service) Battalion; 2 October; Unknown; Outtersteene Communal Cemetery Extension, Bailleul.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Robert Mack; Northumberland Fusiliers, 17th (Service) Battalion (NER Pioneers); 2 October; 24; West Vlaanderen Cemetery. Corporal William Herbert Malcolm Elliott; Wellington Regiment, New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 3rd Battalion; 3 October; 30; Brandhoek New Military Cemetery No. 3.

Sapper Alec Munro; Royal Engineers, 469th Field Company; 3 October; 19; Mendinghem Military Cemetery.

Private Thomas Cowans; East Yorkshire Regiment, 1st Battalion; 4 October; 25; Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery.

Private William Curry; Alexandra, Princess of Wales’ Own (Yorkshire Regiment), 10th (Service) Battalion; 4 October; 33; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRifleman Charles William Dixon-Johnson; Prince of Wales’ Own (West Yorkshire Regiment), 1/7th Battalion (Leeds Rifles) Territorial Force; 4 October; 42; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Sergeant Frank Howe; King’s Own Scottish Borderers, 2nd Battalion; 4 October; 22; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Private James Lee; East Yorkshire Regiment, 1st Battalion, B Company; 4 October; 20; Hooge Crater Cemetery.

Private James William Lorimer; Northumberland Fusiliers, 12th (Service) Battalion; 4 October; Unknown; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPrivate Herbert (Bertie) Gowans Rutherford; East Yorkshire Regiment, 1st Battalion; 4 October; 19; Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery.

Private John Storey; Alexandra, Princess of Wales’ Own (Yorkshire Regiment), 10th (Service) Battalion; 4 October; 32; Tyne Cot Cemetery.

Private James Dickson Wallace; Alexandra, Princess of Wales’ Own (Yorkshire Regiment), 10th (Service) Battalion; 4 October; 29; Tyne Cot Memorial (Tyne Cot Cemetery).